Learn more about the process and purpose of adapting Merry Wives with Playwright Jocelyn Bioh and Dialect Coach Dawn-Elin Fraser.

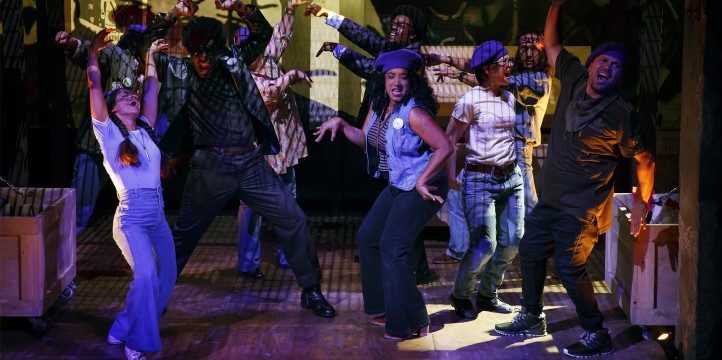

There is a language to New York City we expect to hear on a summer night at The Delacorte Theater: helicopters whirring above house seats; dogs barking “hello” from outside the gate; groups of friends, families, and lovers playing music that scales the walls of the open-air amphitheater. What changes every year, however, is the language of a new, Free Shakespeare in the Park production. This go-around, Lortel Award winner Jocelyn Bioh spearheads an adaptation of The Merry Wives of Windsor. The time? Now. The place? 116th Street in South Harlem, only a few train stops away. After an unprecedented year of theatrical shutdown, this play is the first to reunite in-person audiences with The Public’s artistic programming in the Park and injects the Bard’s classic comedy with new life and a whole new language.

BRITTANI SAMUEL: The contemporary references woven into this production earn some of the loudest laughs. You’ve updated a centuries-old story with jokes about LeBron James and sugar mamas! How did you decide where to take liberties with Shakespeare’s script?

JOCELYN BIOH: We developed a rule of thumb: whenever there was something that absolutely did not make any sense to me, especially in the context of the world we are living in today, I had permission to rewrite it or alter the sentence structure. Basically, if I didn’t get it, we changed it!

BS: Dawn-Elin, what made you want to sign on?

DAWN-ELIN FRASER: Coaching Free Shakespeare in the Park is just one of those holy grail jobs and I love that Jocelyn’s work centers Black joy. I felt prepared, but of course, the main question was: how do I teach speech when we have to wear masks in the room? So much of the work is looking at shapes, demonstrating sounds, and making micro-adjustments to the musculature of the face. We did a lot of it over Zoom so actors could see my face and vice versa—a challenge, but one I was excited about.

BS: Each actor adopted a distinct accent for his or her or their character(s). What purpose did this serve

JB: The original Merry Wives is a pretty nationalist play. Dr. Caius, for example, is from France and the characters mock his exaggerated accent. By setting the show in a multicultural African community, we’re exposing something different. Our Caius can still be a French doctor, but now he’s from Senegal which was colonized by the French. When we get specific in dialect, we show the diversity and history of the Black diaspora.

BS: I have a theory that Black people belong in the theater. It seems like music and drama are embedded in our speech from birth.

DEF: Yes! And Shakespeare’s language is especially predicated on rhythm; the rhythm is the main thing. In my opinion, nobody understands rhythm better than Black people. Period.

BS: It is not just what the actors said, but how they said it that truly delivered meaning. So much was relayed in an “aye” or “eh-heh.” How conscious of this were you?

JB: Those kinds of language interjections are all written in. Africans are expressive and I want actors to have an understanding of how they should punctuate a point. I’m obviously working with this cast but hopefully, in the future, another theater or school will want to do this particular production and they’ll have a guide.

BS: Shakespeare is known for introducing common words to the English language, but after watching Merry Wives, I was reminded that Black people have invented a hell of a lot too. What do you want audiences to take away from this production?

JB: It’s exactly what you said. We not only give to the culture, we create it. That’s why, regardless of whether you’re an immigrant or first-generation or a Black American with deep roots here, you understand why people want to siphon out of our pot. I hope that people who are from this community or similar communities take note of this: we can fold into this old world and still elevate it.

DEF: I think our nation is in a battle for its soul. And this production is important because it demonstrates that there are different ways to be in that battle. Some battles are won with a push—out in the streets marching, campaigning, and organizing online. Other battles are won with a pull—introducing young Harlem to jazz, Alvin Ailey, and now, Merry Wives at The Delacorte.

MERRY WIVES is running at The Delacorte Theater through Saturday, September 18. Learn more about free tickets.

BRITTANI SAMUEL is an Arts and Culture writer currently based in New York with bylines at OkayAfrica, InStyle, American Theatre, and a few other places on the Internet. She can be found on Instagram at @brittaniidiannee.

This piece was developed with the BIPOC Critics Lab, a new program founded by Jose Solis training the next generation of BIPOC journalists. Follow on Twitter: @BIPOCCriticsLab.

Pictured: Susan Kelechi Watson and Pascale Armand. Photo by Joan Marcus.